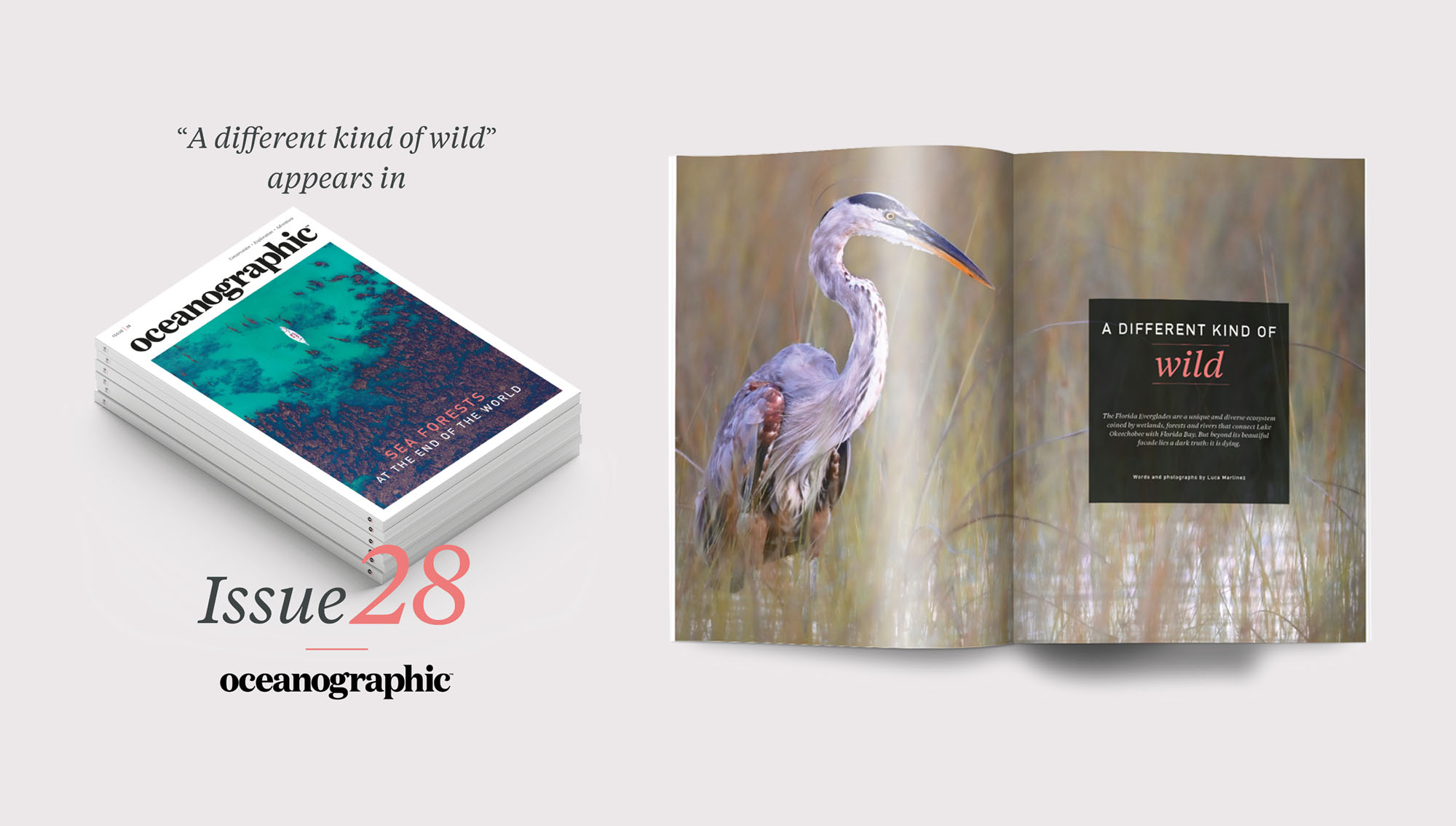

Oceanographic Magazine: Issue 28

WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY LUCA MARTINEZ

05.30am. My dad and I park outside the gates of Shark Valley, a 15-mile paved road meandering through the heart of the Everglades. Keeping left, we start down the trail illuminated by our headlamps. With visibility of no more than 20 feet, our steps are measured. In the far distance, the faint reddish horizon delicately reveals itself. Cicadas screech, pig frogs croak, and a sea of sawgrass sways in the morning breeze. Nature’s symphony is in full surround sound, made all the clearer against the early morning darkness. As the sun rises, it gradually shows a world remarkably different from the uninspired version in my mind. Tens of thousands of tree islands sit on a boundless river of seagrass spotted by mirror-like pools of fresh water. The magnitude and elegance before me takes my breath away. This is the moment my love affair with Florida’s wetlands begins…

My favourite mornings are those scattered with sheets of early fog that fill the emptiness in between. I search for native land where cypress turns to pond apple and pop ash. I seek the sloughs, low-lying areas of earth that channel water through the Everglades. It’s in these sloughs, waist-deep in the black water, where I see and feel most. With no control over the environment surrounding me, immense trust is formed. Where else in this digital world do we feel such vulnerability? It’s a privilege to film and share an ecosystem known to so few where nature conceals countless untold tales. Perhaps that is the beauty of the sloughs.

Life here exists in mystical layers. Beneath the water-lined surface, disguised as a stick or a log, the Florida gars glide silently. Alligators lay motionless as if posing beyond the lights of my underwater camera rig. Every footstep depresses the lemon bacopa lining on the peat bottom. Breaking the moment’s gravity, a rare pair of playful otters twist, turn, and splash. Following the tentacled roots of flora unrecognised, I look up, the inhalation lasting several unintentional seconds. The ghost orchid, the world’s rarest, looks back at me with soulful wisdom as it dances, hovering over the duckweed.

I’ve spent the last three years exploring South Florida’s wilderness and learning about its history. This ecological community is misunderstood, and many consider it a second-class ecosystem. As a result, the human impact is undeniable; beyond its beautiful facade lies the reality that this place is dying. In my travels to and from these pristine sloughs, I’ve realised that the impending danger comes from the things we no longer see.